The Inner Game of Knowledge Work

There are two paths to cognitive control, and they're both counterintuitive

Many organizations fail due to lack of follow-through. Companies, dreams and even people die because the ball got dropped too often. While the pathologies of the organization are many, at an individual level follow-through can be addressed — it comes down to how well you focus your attention.

High-output individuals prioritize and execute; they steer and sustain attention; they keep promises even when it involves doing hard things.

In a previous post, I shared how you can reduce digital distraction to regain control of your brain — that was a first step. The second has to do with your brain itself, and how it behaves when confronted with a disagreeable task.

Your brain is naturally avoidant

Many people become avoidant when faced with something hard, complicated or tedious. They choose the second-hardest thing on their list, or engage in pretend work like checking their phone for work messages again. This is the mild flipside of addiction. We are all scanning the space of possible actions before us, surveying its heatmap of pleasure and pain, and choosing the candy. But doing worthwhile things means doing hard things, and work, like the best education, means turning toward discomfort in order to achieve mastery and deliver what’s needed.

This post explores the inner game of knowledge work. It presumes that you've cleaned up your digital environment, and in the stillness that follows, you're left with your monkey mind. This mind daydreams, ruminates, rehearses what you'll say to so-and-so, wonders whether you should get another coffee, and makes you cringe for something you did years ago. In other words, it's not on task.

In knowledge work, there is only one thing that matters: knowing what you're paying attention to right now, and doing it on purpose. This post will give you some tools to achieve that.

Path 1: Acceptance, not combat

Unlike external distractions, which you can cut off at the root, you must take a very different approach to your thought stream. If you decide to fight your stray thoughts, then your brain simply engages in fighting, and you've lost the battle by the very act of making it a battle. This is the paradox: you only attain the mind you want by noticing and accepting the mind you have.

The light you train on your thoughts must be nonjudgmental — like describing traffic: “there's a red car, there's an ice cream truck.” In contrast, saying “there's a crappy red car that shouldn't be on the road because it's spewing exhaust; there's an ice cream truck full of calories that will make me fat,” is judgmental. The goal is to observe without judgment. State a fact, don’t add a value.

By simply acknowledging "I'm having a thought about X," you've stepped off the thought train that captured you, while remaining non-judgmental. You’re not fighting, but you’ve shifted the locus of your awareness and won yourself some space. This is neutral attention.

Your thoughts are invisible, sadly

You may have noticed I'm using a lot of metaphors: the light of attention, the stream of thought, the locus of awareness. It’s hard to describe what’s invisible, and sometimes useful to imagine the mind as spatial, since that’s what we know from life. (Julian Jaynes thinks that’s how humans invented consciousness, with metaphors.)

Obviously, our brains are a biochemical soup, recursively producing thoughts and feelings—using the output of one thought to generate the next. Each of us exists within this thought stream, often identifying so closely with it that we fuse with our thoughts. We think they is us. And all of this occurs inside our skulls, making it impossible to capture the action on video for replay.

But we can move within those thoughts, and tug at the veil that conceals them.

Indeed, the greatest challenge of this inner game is making our thoughts visible. (That is, making the inner game an outer game in the course of work, rather than when you deliver the final artifact.) The thought-naming exercise is one way to do that. Journaling also allows you to think outside your head; it's aptly called reflective journaling, because a mirror lets us see parts of ourselves our eyes can't directly observe.

Creating intermediate artifacts from your thought stream can help; i.e. writing and drawing what’s coursing obscurely through your mind. Paper and pencil offer more flexibility than the two-dimensional ticker tape of a word processor, though both externalize mindspace effectively.

Simply put, the brain is no place for serious thinking—you need to get ideas out where you can see them. Seeing what you’re doing in any domain enables you to create feedback loops so that you can change and improve. The domain of thought is singularly elusive. But once you see it, you can pay better attention, and attention itself is curative.

Getting the inner game out

There are a few exercises beyond thought-naming that may be useful.

Counting: you can count your breaths like Buddhists do. One through ten repeating.

Walk and count your steps. Attention on the soles’ contact with the ground.

Tap your hands on your thighs and count each strike, alternating hands.

Slowing these activities to half speed may add enough novelty to hold your attention longer.

By focusing your attention on one thing, you'll notice other thoughts emerging alongside—like dolphins accompanying a swimmer.

The real goal of these exercises is to understand exactly what happens when your mind veers off course—that is, to uncover the chain of mental events that starts with “I need to do X” and ends with “Why am I staring at my email inbox and where did the last 20 minutes go?”

An example

Consider this scenario: You need to do something like 'collect a few dozen logos and place them in a slide deck.' This task is tedious and difficult to automate because you need to track down specific logos one by one, convert them into images with transparent backgrounds, paste them into a presentation file, and then position and size them to look appropriate. Attractive, even. It requires domain context, some taste, and interacting with multiple GUIs, but not a lot of intellectual power.

While contemplating spending the next couple hours finding, modifying, and positioning logos, you might check your inbox, then your phone, then a tab with a news story you opened earlier. This is avoidant behavior occurring because of an aversive task. However, you must complete it—the presentation is due soon for a crucial meeting that will determine the fate of your team, and your job depends on delivering it.

Now, you can't delete thoughts; there's no eraser. We're all caught in a recursive stream of thoughts and feelings, spawning more as we go. You won't stop them by plugging the dam with a finger, and they only gain strength if you fight them. But you can notice them—and you can add something to them.

Here's how you notice and add:

First, bring yourself into the present moment:

'I'm sitting here in [PLACE] at [TIME] on [DAY], and I'm having a thought that X and a feeling that Y.'

For example:

X could be, 'I need to check my phone.'

Y could be, 'I'm upset because person Z disagreed with me online.'

By doing this, you tap into the present and pay nonjudgmental attention to what's happening in your mind. This practice helps you step outside your thought stream and serves as a form of exposure therapy.

"I'm going to remember my purpose here, which is D—e.g. ensuring my family has a safe place to live so my children can grow and reach their potential."

"Because I care about that, I'm committing to TASK—e.g. finding these logos and placing them on the slides."

This mental aikido move is part of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Here’s Dr. Jonathan Bricker explaining it in a TEDx video.

Getting yourself over the action line

From a behavioral standpoint, you're exposing yourself to aversive feelings while stoking your motivation by recalling your deeper values, making action more likely. By calmly facing discomfiting thoughts and feelings, you drain them of some power, decreasing the likelihood that they will block you as strongly the next time.

This approach may help you cross the action line and take the next step: breaking down a vague, tedious project into a sequence of small steps, each trivial to accomplish—making action more likely.

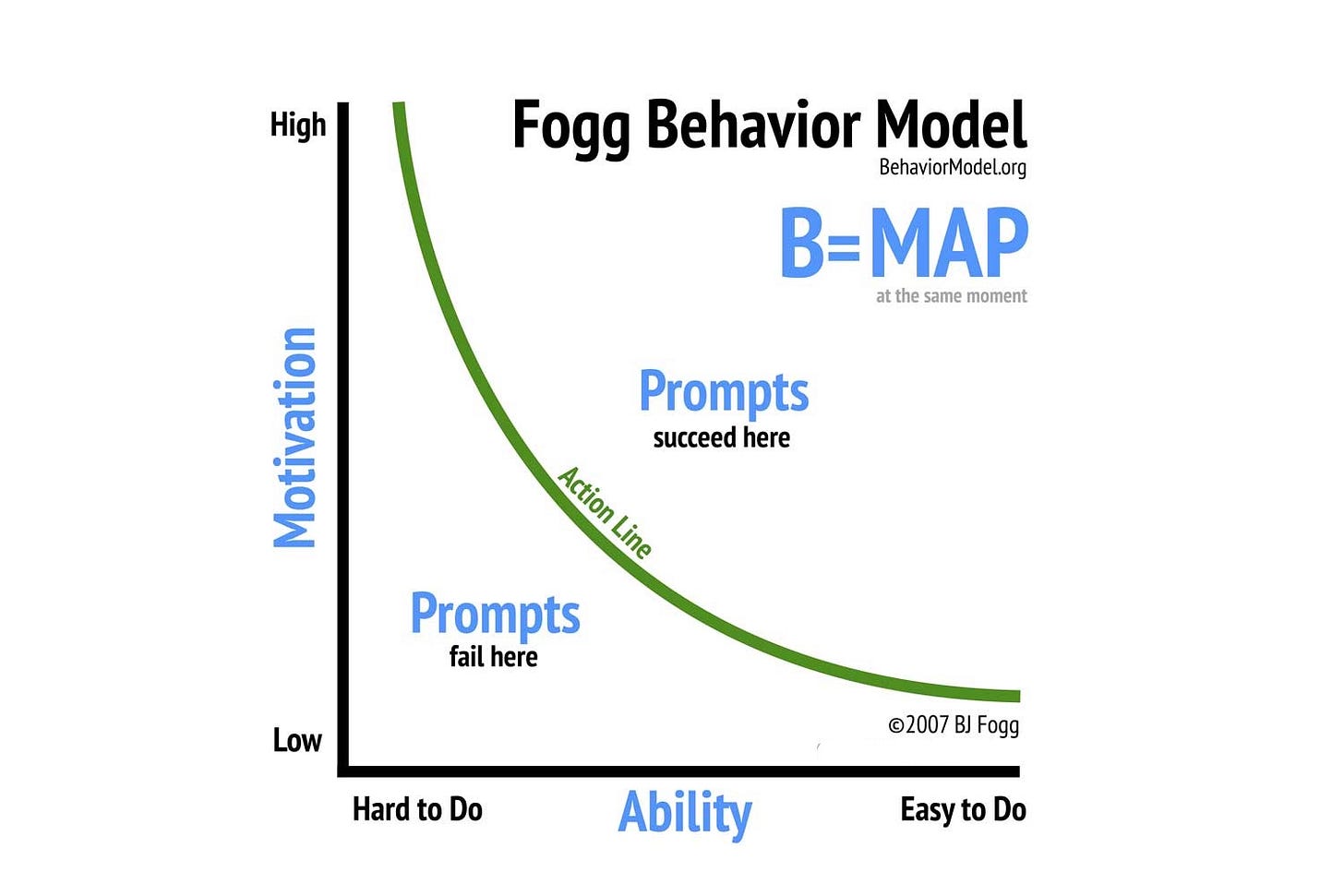

These strategies—increasing motivation, decreasing perceived difficulty, and draining the power of aversive mental currents—are drawn from Dr. B.J. Fogg's Tiny Habits and his behavioral model, the motivation-ability curve.

You can read more about the model on B.J. Fogg’s site. The whole idea is to get yourself over the action line by making the task at hand easier to do, increasing your motivation whenever possible. Prompts are things that remind you do do something, and can be placed strategically through out your daily routines where you live and work.

Path 2: Change your body-state to change your mind

If these cognitive moves don't work, you can approach the problem from the side by altering your body-state.

The three best ways to immediately change your body-state are:

Alter your breathing.

Increase your heart rate with exercise.

Change your body's temperature—using a sauna, an ice plunge or a cold shower.

Let’s dig in:

Anyone can box breathe. You breathe in deeply for four seconds, hold it for four, breathe out for four, and hold it for four after the outbreath. Repeat until calm. (Don't do this while driving or bathing, you might faint.) Fun fact: this is one of the few ways our conscious mind can control what’s usually an involuntary process, and it happens to stimulate the vagus nerve, which has a calming effect. (Here’s a free, super simple Web-based breath trainer I made that walks you through it.)

Almost everyone can take a brisk walk, or hop on a tread mill for 4 minutes, or do a few jumping jacks. Short bouts of acute aerobic exercise that raise your heart rate have been shown to vastly improve executive function (EF), by increasing the flow of blood and nutrients to the pre-frontal cortex, and stimulating neurogenesis and growth factors to support neuroplasticity. This is the single most important thing I have done to increase executive function.

Most people can turn their shower to cold and stand under the chill. With a little searching, they may find a sauna and ice plunge nearby. I plunge, and I get a plunger’s high, which can last for one to two days depending on the chill and length of the plunge itself. Advantages: It’s cheaper than cocaine and doesn’t involve prison time.

Other techniques to focus the attention include juggling, balance boards, or playing music. Balancing exercises, especially ones where you lose your balance, stimulate adrenaline, which is great for spiking attention and consolidating learning. It is no coincidence that Claude Shannon, the inventor of information theory, was an avid juggler and unicyclist.

Finally, there is non-sleep deep rest, or yoga nidra, which is thought to allow the brain to clean itself of some of the chemicals that build up over the course of the day and cause fatigue and inattention.

A personal story

Some of this advice may seem familiar, especially to people who have tried meditation or read the teachings of Buddhism. Here is how I came to it:

When I was a teenager and still in high school, I became depressed. Not “kind of sad” or “kids these days” depressed, but clinically depressed in a way that would lead me to drop out of college because I could no longer formulate a written sentence. I spent several years working in pizza kitchens while taking a successor to Prozac, baffled by a brain that was out of my control.

During those years, when my brain seemed to be made of pain and pumice, I held tight to the idea that I was not my thoughts or feelings. That mental distance kept me afloat.

At the same time, physical exercise — running many miles at a time through the mountains — helped me catch glimpses of my former self. Without realizing it, I was bootstrapping my brain’s biochemistry.

Eventually, by luck, I entered a Zen community, lived there for a year, and learned how to breathe.

So these two practices — observing my thoughts, and changing my body-state to change my mood — are lessons earned through hard experience. I’m not hawking recycled advice as a productivity guru, but attempting to the paths that led me out of the dark woods of my mind.

OK — what’s next?

If you’re saying to yourself right now, “These are great ideas but how do I weave them into my life?”, my best answer is to read the work of B.J. Fogg, cited above and below. He will show you ways to find the right behaviors and attach them to your present routines. He has for me, and it’s been a liberation.

All of the behaviors described above can alter your biochemistry and neurological energy, which is the fuel of knowledge work. Doing them one by one throughout your time at the office, during breaks from knowledge work, is a good way to restore your attention for another bout, and squeeze more out of each day.

As the years have passed, I’ve found that the ideas which lifted me out of depression also work in the workplace, where many face their own struggles, whether or not they are depressed. They are good not just for crawling out of a black pit, but for realizing a greater goal. I believe attentional management is one way people can come into their full human potential, and do the things they say they dream of. And it would a damn shame if they didn’t.

Books & Posts

Attention Span, by Gloria Mark

The Inner Game of Tennis, by Tim Gallwey

Tiny Habits, by B.J. Fogg

The Liberated Mind, by Stephen Hayes