Everything I Know About Management I Learned Coaching 5 Year Olds

If we trained knowledge workers like we do kids, we'd have better orgs

I have a five year old son and I coach him: baseball in the spring, soccer in the fall, swimming in summer (less formally) and skating in winter.

While I'm not a huge sports watcher, moving around together outside is a good way to connect with the youngs. About a year ago, being on a team seemed like a good way to keep doing that. So... coaching!

The great thing about coaching five-year-olds is that everyone knows they don't know much, and you can see everything they do.

This is very different from business, where everyone pretends they know stuff that is hard for a non-expert to confirm or refute, and all you see are the outcomes of their work after a long period if you're lucky. (But outcomes are hard to disentangle, since so many factors lead to them, so many people contribute, and credit is hard to assign.)

Even attempting to ascertain another person's true skill may be considered rude. Moreover, obtaining that information via testing in, say, a hiring process is pretty time-consuming.

But five-years-olds on a field are visible; everything they do you can see. They are making tangible mistakes on their path to building skills. And by coaching them, you can help them make fewer mistakes.

This aspect of visibility and tangibility is a big deal, and hard to replicate in say, knowledge work, since so much of it happens in the mind. Sure, you could say that knowledge work produces artifacts, but the important thing about skill building is in what happens before you hand in your assignment. It's the path by which you get to the product. (Big open question for me: Can we make attention visible in order to debug its dysfunction?)

Principle 1: Every skill requires a bunch of pre-skills that you probably haven't thought of.

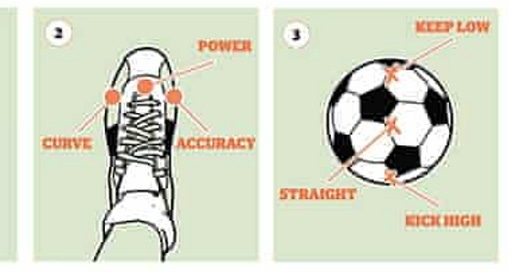

- During the first practice, everyone was toe-kicking the ball, which is bad because you can stub your toes, and you simply can't control where the ball goes. So you teach kids to do side-kicks and laces-kicks with a lot of reps, doing your best to make it fun, which brings you to a place where they might someday shoot and pass to each other well (a more complex skill involving several people at once). That is, you probably need to start teaching any skill by conveying an idea much more basic than you imagined, like the difference between your goal and the other team’s.

- When actions are visible, it's easier to break them down into subtasks and start by learning those. For example, when kids learn to read, they actually need to know how to hold the book right-side up, and which direction to turn the pages. They need to grasp the idea that the squiggles are letters and that letters make sounds. These are pre-literate skills. Every big headline skill is like that.

- The U6 experience has highlighted for me how little effective training and coaching happen in companies. Most organizations are running in emergency mode where they hire people who can hit the ground running, and never get their heads above water enough to improve how they work, since they are under constant deadlines to deliver now. Many top performers hoard their rare skills so as not to make themselves replaceable. Many companies know that "skills have legs"; that is, when you train someone up, they can walk across the street to the competition. Most novices are ashamed to admit what they don’t know. Coaches themselves may be tasked with giving significant negative feedback, which not everyone can take. So there are multiple, severe disincentives to organizations getting collectively better, which leads to our present conditions.

- Given the lack of proper training, companies that want to succeed should focus acutely on selecting the right people, but many don't manage to select well, which leads to org decay and expensive firings.

Principle 2: Small teams are tightly coupled. The interdependence is intense.

- Five-year-olds play 3 on 3 games in the U6 league. So every player has two functional teammates at any point in the game. But younger five-year-olds are much less developed than older five-year-olds pushing six, since that single year accounts for 16% of their lifetimes, so you get a ton of variation in skill, strength and focus. If one player can dribble the ball, while one of their two teammates prefers to sit on it or suddenly remembered he was thirsty and left the field, the game is already lost. Chain, weakest link, it's all true.

Principle 3: The same team needs different skills at different stages. Being good at one stage isn't good enough to get a project over the line.

- Our team happens to be pretty good at clearing the ball from the goal; they are pretty bad at taking the ball down the field. So we lose a lot and I, at least, know why.

- The business equivalent of moving from one goal to another is project lifecycle, or even task lifecycle (if you consider the subtasks and pre-skills necessary to do any given thing). People in the ADHD world know that you can be great at a few things, and still fail to press send once the artifact is complete. Likewise, groups working on projects together need to be good at, say, clarifying their goals at the beginning; communicating and executing on their commitments in the middle; editing and polishing at the end.

To sum up, there’s another way we could do business. It would be transformative for the people who skilled up, as well as their employers. Change is a skill that must be acquired on an individual and organizational level. A lot of people and groups aren’t great at that sort of change, or only achieve it under intense negative pressure to change. Indeed, instances of great coaching are rare, and coaching really works best when it goes beyond a single player to teammate groups who deliver something together, because a functioning team is one of the most powerful things in the world.